vol. 17 - The King of Comedy

The King of Comedy (1982)

directed by Martin Scorsese

Dalton Norman

The King of Comedy | 1982 | dir. Martin Scorsese

"Is a dream a lie if it don't come true? Or is it something worse?"

—Bruce Springsteen

The beauty of art is that the artist, once completed with the project, has no control over what the art means to the audience or how they interpret it. Some artists vehemently resist certain interpretations of their art (see Georgia O'Keeffe) and other are intentionally verbose, only giving the audience a raised eyebrow and a big shrug (see David Lynch). I love to see through the text, through the subtext, and into the impossible realm of what I call personal sub-subtext. What that means, essentially, is that certain pieces of art, especially film and music, can grab my imagination and send me down a road of interpretation that the artist probably never even contemplated when putting pen to paper or paint to canvas.

Instances of this phenomena are rare but they are most likely to occur in situations where the piece of art shows just a little bit too much of myself in it for comfort. Recently, a film (that's nearly forty years old, mind you) grabbed my attention in just that way and sent me down a rabbit hole of sub-subtext that I'm sure would infuriate the filmmaker. I was combing through the Martin Scorsese filmography, picking up the pieces I had missed and filling the gaps in my knowledge. Films like After Hours (1985) and The Color of Money (1986) were pleasant surprises and I was definitely guilty of shoehorning Scorsese into the "hey, that guy only makes mobster movies" corner that so many others put him in. One film from Scorsese's 1980s catalog took hold of me with a particularly strong grip. Not because it was a better film than Taxi Driver or Raging Bull, but because I caught onto its sub-subtext and I couldn't stop thinking about it even weeks later.

In 2019, boner comedy director Todd Phillips released Joker, an interesting reinterpretation of the thoroughly played-out comic book character. In a year that seemed to intentionally spell the end of the superhero film, at least spiritually, Joker caught on well and the internet was alight with memes that eventually turned into decent critical and box office returns for the film. Being perfectly honest, I didn't see the film and I had very little interest in it. Almost immediately after its release, whispers began about its similarity to the films of Scorsese (stoked by Phillips's own admission), particularly a hidden gem from 1982: The King of Comedy.

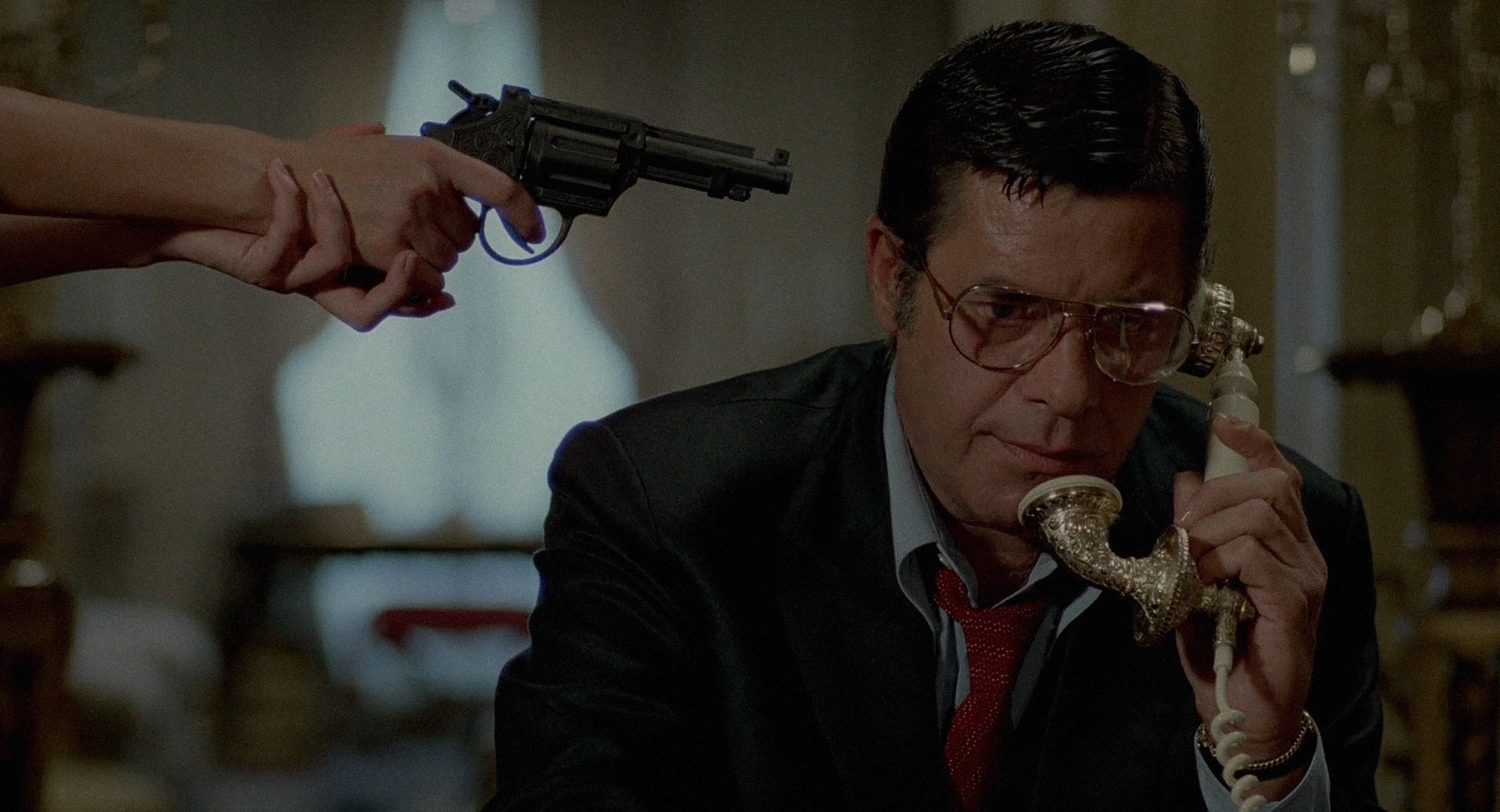

By 1982, Scorsese and Robert De Niro had formed an artistic partnership that would eventually define both of their careers. Scorsese had evolved into a master of cinema who came on at the tail end of the new Hollywood generation and catapulted himself off from successes of the ‘70s into a guaranteed hit maker in the ‘80s. De Niro had stretched his range through the seventies and had settled into his place as the standard of quality performance, becoming famous for his commitment to complex characters and method acting. In The King of Comedy, De Niro plays Rupert Pupkin, a 30-something aspiring comedian who believes his big break can only come if he gets to appear on the Carson-esque Jerry Langford Show (with Langford played by Jerry Lewis). He teams up with another woman obsessed with Langford and together the pair stalk, and eventually kidnap, the talk show host in an attempt to get Pupkin on the show.

The film was critically well received but failed to move the needle at the box office, losing nearly 17 million dollars all told. The film, though excellent, straddles the line between comedy and drama and it was Scorsese's first stab at humor after Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. Audiences weren't ready for a funny Marty, and they showed it by not going to the theater. It is an incredibly well-crafted film, featuring a perfect concoction of characters to create the strange brew of the story. Every person, no matter how unreasonable in their goals, is sprinkled with a dash of humanity that keeps you engaged and at the very least neutral towards them. It would have been very easy to make Pupkin an entirely unlikeable schmuck, or irredeemably weird and unpleasant like the 2019 Fred Durst “classic” The Fanatic did with Travolta's Moose character. Instead, Pupkin, though strange, is just likable enough that he never comes off as a villain. Similarly, Langford, who is at the epicenter of the obsession, never passes into unreasonable territory as well. We don't get a scene of Langford being an ass to someone to set him up for his inevitable comeuppance—instead, he reacts reasonably to the ordeal and we even get glimpses into his own sad personal life.

Obviously, the film is a cautionary tale about obsession and how scary it is to be a celebrity, and how even though Langford is a star, he leads a lonely life. But, as a person who has spent my immediate post-collegiate years staring at the impenetrable wall of showbiz looking for a way in, I can't help but sympathize with Pupkin. Obviously, kidnapping a celebrity and holding them hostage for your big shot on the air is ill advised, but I can't help but wonder whether circumstances pushed Pupkin to do what he did. The first important piece of my interpretation of the film is that he is given a partner in crime who is the true measuring stick of irrationality. She is sexually obsessed with Langford and somehow believes that they are meant to be together. The purpose of her character may have been to show Pupkin's own guilt by association, drawing parallels between their obsessions, but I don't see it that way. Instead, I see her character as a way of showing Pupkin's moral innocence. He wants nothing from Langford specifically, instead he just wants a shot at Langford's platform. Jerry just has the unfortunate distinction of being a gatekeeper as someone who unwittingly controls the fates of many aspiring performers. In my view, the film asks a very important question; who decides which dreams come true?

I'll be honest, screenwriter Paul D. Zimmerman and director Martin Scorsese were most likely not thinking about that question when they made the film. When speaking about the project, they mostly mention “Autograph Hound” culture and the obsession with celebrity as their inspirations. Therefore, as previously stated, my interpretation of the sub-subtext is entirely my own, based exclusively on personal emotion and experience. The film does however give me enough tidbits to ground my theory in some sort of logic and I didn't pull my interpretation entirely out of thin air or the swirling maelstrom that is my professional jealousy.

Capitalism is a real kick in the ass. I have a hard time writing more than a few paragraphs without blaming all the world's ills on the socio-economic system, and in this case, I think it is to blame once again. Rupert Pupkin's backstory is left intentionally vague. We know he is in his thirties and lives with his mother, two facts used by the filmmakers to unfairly try to disqualify him from our sympathies. Under capitalism and backed up by its best friend the patriarchy, we view men who don't make six figures as failures, and anyone who hasn't “made it” by thirty is the worst thing of all: a loser. Pupkin may not necessarily have a passion for performing in his heart—he may, but he may also view being a celebrity as the only way to truly make it in this country. To be fair, every day we are inundated with images of what a successful person looks like, and that person is usually a celebrity, actor, or sports star. Capitalism has convinced Pupkin through a hard life of personal and economic strife that the only way to support himself is by becoming a mega-millionaire superstar and every year that passes only proves that more true.

Life under capitalism is such that the threshold of a “decent life” has been pushed further and further up the income ladder that nearly forty years after the release of the film it seems almost unattainable for millions of Americans. If Pupkin truly had a passion for performing, capitalism has succeeded in sucking every ounce of joy out of the prospect. By monetizing every hobby, skill, and performance art, the mad dash for cash has taken an elephant gun to the idea of a passionate life. Instead, most industries are filled with people who do it not because they want to but because they view it as the only way to make enough money to survive. The advantage is immediately given to people who are more well off because they don't have to worry where their next meal is coming from. For the millions of Americans like Pupkin, it is hard to get your ten thousand hours in if you have to work twelve hours a day in a factory to make ends meet.

On top of being soul crushingly unfair, capitalism is the ultimate source of social gaslighting. Capitalism has produced such hits as “you have to go to college to get a good job...and if you can't afford the loans, you shouldn't have gone to college” and “capitalism is great because you can be whatever you want...and if you didn't want to be poor you should have become a doctor or lawyer.” The myth of the American Dream falls apart under even the flimsiest analysis and people like Pupkin slip through the cracks on the daily. Now, I understand that capitalism has a lot of fanboys and even people who are more progressively minded may be reluctant to agree that the American Dream is a lie. Often those people speak to their own successes as proof that it works. I challenge those people however to admit whether the successful life they have is truly the life they wanted or simply the best possible path towards economic stability. I'll admit that Pupkin doesn't have to be a comedian; there were more opportunities in the ‘80s for an able-bodied white man to make it in a decent career than there are today. I will argue, however, that that exposes the hypocrisy of Pupkin's situation and capitalism in general. Why does Pupkin have to give up on his dreams? Why does Jerry Langford get the big break and Pupkin has to watch from the sidelines? Those are both unanswerable questions, but those thoughts are what spurred my analysis. I watched the film in abject horror worrying that someday I could be Pupkin. As a writer, there's never a guarantee that what I write could support me and it is very easy to fall into the toxic positivity trap of believing that the big break is only right around the corner.

In a way, Pupkin is buried by a double whammy of two traps set by capitalism in a deliberate attempt to break our minds. First, the aforementioned toxic positivity trap leads the sucker to believe that if they only work harder they will succeed eventually. All you have to do is be positive and keep smiling and things will all work out down the road. Toxic positivity, I believe, was devised to keep the poor people from realizing they are getting an unfair shake and rising up. Similar salves (opiates if you will) have been applied throughout history, namely religion and an overabundance of entertainment. Pupkin is being told to keep at it and never give up and yet he is not unaware that he is sliding into his thirties and making a career restart is nearly impossible that late in the game.

The second of the big double whammy is what I call the “ambition paradox,” in which a person is told that the only way to get ahead in capitalism is to be cutthroat, no compromise, and full speed ahead in their endeavors. Often, we are encouraged to circumvent the traditional structures and rules to make ourselves stand out. Windbags often go on and on about college dropouts like Gates and Jobs as examples of ambition personified. What isn't mentioned, and thus what forms the paradox, is the fact that the average Joe is punished immensely for their unorthodox ambitions. Just try getting a job today that pays a living wage without a college degree.

The latter of the two is what I believe pushed Pupkin to pursue his ransom idea. By showing his gun was unloaded the whole time, it is revealed that Pupkin had no intention whatsoever in harming Langford. Ultimately, I believe he would have let him go immediately if he met any sort of physical resistance. Though his plan works and he does make it on the show, it is a hollow victory and the working-class man is forced back down into the station of life he was assigned to at birth. Pupkin got a brief glimpse of the sun before the capitalist programing fixed the bug and booted him.

The ending is the biggest joke in the film as far as I'm concerned, and it points to one of the few ways to become famous in this country: to become a criminal. Pupkin wanted nothing more than to be somebody and that is the usual cry of the oppressed. Often, criminality, besides its financial motivations, is the one surefire way to achieve Somebody status in capitalist America. When a person acts out, it is usually from an unmet need. A baby cries because it is gassy, an adult gets into an argument over something small because they can't fight what is truly bothering them, and criminality is no different. Pupkin has spent his entire life being pounded down into the nobody mold when all he wanted from life was to be somebody. He dresses flashily, he hounds celebrities for autographs, and he wants to be the King of Comedy because those things give him the illusion of being somebody.

I'm not naive enough to believe that everyone's dreams can come true. I understand that some are entirely unattainable or unrealistic, but I think it is important to analyze the nature of someone’s goals and understand that there is usually more than meets the eye when it comes to dreams. Why does Rupert Pupkin want to be famous? Why shouldn't he? He may be a hack comedian, but surely there are plenty of successful hacks. How many millions of Americans would light the world on fire as comedians if they got the chance? How many minds hold the key to the future of science but are trapped behind an impenetrable wall of expensive colleges and gatekeeping institutions? Next time you get rejected for a job opportunity ask yourself this: why does that person get to decide whether my dreams come true or not?

In my mind, The King of Comedy perfectly lampoons the biggest lie that capitalism tells us: that you are in control of your own life. Pupkin tries to take control and is punished for it. Jerry Langford controls Pupkin's life, or more specifically the dozens of Langfords in the world that essentially controls who lives a good life and who dies poor and destitute. Ask yourself another question: who am I? A Pupkin or a Langford?

Dalton Norman is a novelist and filmmaker from Orlando, Florida currently living in Los Angeles. He writes for geek content websites but his true passion is writing novels and screenplays. His debut novel Hotshot is available on Amazon.