vol. 14 - Wild Zero

Wild Zero (1999)

directed by Tetsuro Takeuchi

Alex DiFrancesco

Wild Zero | 1999 | dir. Tetsuro Takeuchi

When I was twenty-two in the early aughts, I worked in a small town used record/video/CD store. Our record library was expansive, spine-out, curling through the shelves of a large room, and our DVD and CD collections were also impressive, if smaller. My coworkers were exactly the kind of guys you imagine working with in a record store from films like High Fidelity. My favorite coworker was Rich, a guy ten years older than me with obscure taste. Every movie I had seen that I was sure was weird and off the beaten path, Rich knew intricate trivia about. Rich had been a fine arts major in college, made me collages of David Bowie, and informed me of music and film I certainly had not heard of that he knew I would enjoy. It was Rich who introduced me to Wild Zero, the zombie horror-comedy that starred the Japanese “jet rock ‘n’ roll” band Guitar Wolf.

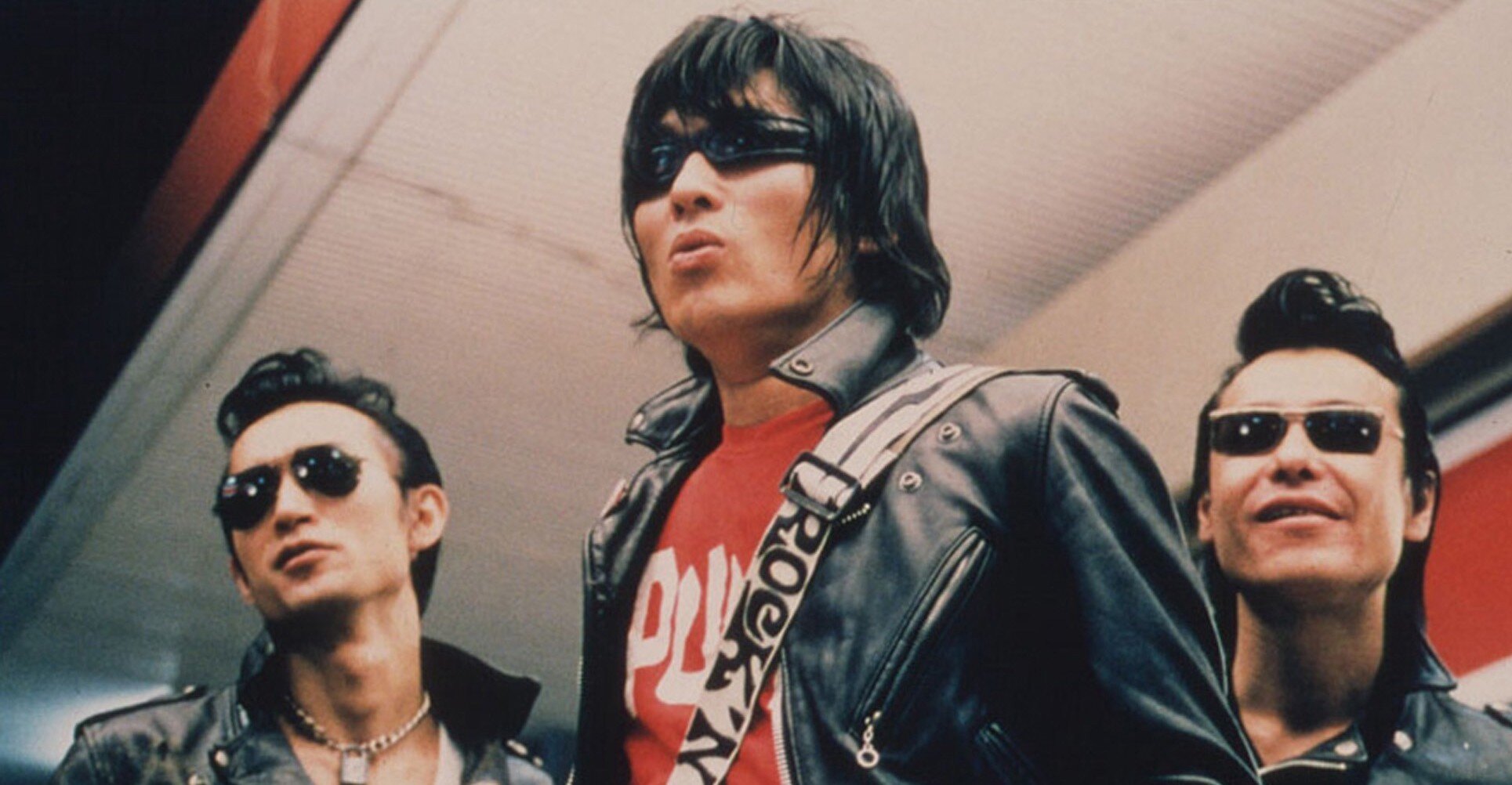

I put “jet rock ‘n’ roll” in quotes because Guitar Wolf invented the term that defined their style: likening their garage rock to the roaring of a jet. As far as I know, they are the only ones who use it, and their screamed lyrics are often a sublime mix of accented English and Japanese. They are cool even if their music is not great, like a Japanese version of the Ramones; even my ID’ing vaguely as bisexual, nascent feminist, still-in-the-closet trans twenty-two year old self could see that. I became obsessed on first viewing of this film, not only because Guitar Wolf was cool, but because the film seemed suddenly to me, then, to introduce that one of the characters was transgender. My closeted, deadnamed persona (I use the term persona because this version of me had no chance at being the real me) was fascinated by trans characters in book and in film, viewing it as a cutting edge and intriguing choice. Or so I told myself. And what was even better was that this film, made in 1999, boldly promoted a message that not only was being transgender okay, but it was blessed with the approval of Guitar Wolf, who proclaimed to the main character Ace when he discovered his love interest’s trans identity, “Love knows no nationalities, borders, or gender!”

I was twenty-two. I was trying too hard to be someone I was not, a woman who pushed boundaries as far as her limited imagination was able, who walked around in combat or motorcycle boots and cuffed jeans, with a belt that had “motherfucker” branded across the back and a rattlesnake head belt buckle. If I was queer (a word that was still a pejorative to me then), it was rock and roll queer, edgy feminine masculinity, an inversion of Bowie. I remember meeting a heroin addict in a bar one night, us flirting and commenting on my shaved head and his long hair with his words, “I like girls with short hair,” and mine, “I like boys with long hair.” There was a queerness in it we couldn’t wade into, couldn’t recognize outside of rock and roll and drugs. But outside of David Bowie, I had never seen rock and roll fuck with gender in the way I was seeing as I watched Wild Zero.

*

I had shaved my head as soon as I moved back to the small town I grew up in from New York City. It was a minor act of rebellion, one that made me giggle when middle-aged women came up behind me in the record store and hedged, “Excuse me, sir?” Growing up, my mother (who certainly had an inclination of my gender variance from a young age, and rejected it), had insisted I wear my hair long. My longterm boyfriend, who I’d split up with shortly after moving back to our small hometown, had always insisted I wear it long. Just before we left New York City, I got drunk one night and cut it off to my shoulders. After our break-up, after I started classes at the local community college, I took an electric razor to my head. I dressed more like a punk than I ever had, more than my musical tastes probably warranted. I didn’t wear poser shirts of bands I didn’t know, but there was a leaning into something that I wasn’t. My long nights spent in front of a typewriter, my getting ripped off by the junkies who lived upstairs when I was trying to get high, my soft inability to know anything about myself—they were hidden by a rock and roll swagger that I had no right to.

Perhaps it will surprise you that the person I identify most within Wild Zero was never Tobio, the trans love interest. Tobio, when I first saw the film, was out of the realm of possibility for me, and as a trans woman, her identity is still not quite my reality. No, it was Ace, the devotee of Guitar Wolf who wants so badly to be his favorite band’s brand of rock and roll cool. It was Ace, a soft boy with a beatific smile who rides an old motorcycle, cuffs his jeans, wears motorcycle boots, and keeps haplessly, accidentally saving the day by bumbling around knocking people out with doors in tense situations. Ace, who after he is knocked out in a fight with a sleazy club manager in the green room at a club Guitar Wolf has just rocked, becomes blood brothers with Guitar Wolf’s lead guitarist (also named Guitar Wolf), and is gifted a whistle to blow if he ever finds himself in trouble and needs the band to save him.

When Ace meets Tobio in a gas station where he accidentally thwarts a robbery, after spaceships have wrought zombies on the earth, any trans viewer of the film already knows she is trans. Her identity is laid out before she even hits the screen, when the camera comes up on a man jumping into a car, screaming, “Weirdo!” and throwing her purse by the side of the road. She picks it up and walks off. Any trans viewer has experienced this a million times, on dating apps where we get banned when people match with us then report us when they find out we are trans; from men or women who were, a moment before finding out our identities, flirting with us in bars. Tobio’s identity is a given to me as I watch this film now, and not just because I have seen it before. But Tobio is not our lead, and Tobio walks onto the screen comfortably who she is. It is Ace, who wants so badly to become, that I read my queer self into when I watch this film.

*

To be transgender is to will a self that only exists inside of you into existence in a world that may never be ready for it. Today, I am not a girl hiding in a swagger and a shaved head. I form my body through hormones into what I wish it to be. I have my hair bleached professionally, and I comb it back into a pompadour much like Ace’s. I buy purple suits and have them tailored to fit my distinctly trans body. I spend my money, when I have it, on gloriously rock and roll leather boots with buckles and zippers, men’s dress shoes, couture kaleidoscope boy’s dress shoes I find for sale on Ebay. I swagger less because I don’t have to posture. The process of becoming is one that gives you confidence, when it takes root, and allows you the choices you always wanted to make.

Ace is not cool, though he wants very much to be Guitar Wolf’s brand of rock and roll. Ace combs his hair with a red rattail comb that Guitar Wolf finds discarded at a gas station at one point in the film and proclaims to be like something someone’s mother would use: uncool. Ace smiles goofily while Guitar Wolf sneers gloriously. At one point, when he and Tobio are holed up in an abandoned building, just before he learns her trans identity, he declares himself utterly unlike his heroes, unable to even play guitar or make music. His identity is a facade, something he saw in the world and wanted for himself. It’s no surprise that when he learns his love interest is trans, he rejects her. Ace is a poser, he knows this, and Guitar Wolf knows this. But there is possibility in this posturing. While trans identity cannot be said to be the same sort of posturing, there is a stage of becoming in transness, too. There is a period of time when you have to will yourself into who and what you want to be. Before I came out, the world around me seemed to know so much more about me than I knew about myself. Guitar Wolf finding Ace’s comb in the gas station and calling it uncool—they could’ve been talking about my cuffed skinny jeans, my motherfucker belt, my rattlesnake head belt buckle. There is a separation between hiding behind rock and roll, and being rock and roll.

But this is something Guitar Wolf never points out to Ace, as few pointed any such thing out to me when I was twenty-two, fucking married couples, doing heroin when I could get my hands on it, pretending to be someone I was not. In the world of Wild Zero, rock and roll has some machismo, the kind that can turn a guitar into a katana and down an invading alien spaceship, sure. But real rock and roll accepts, knows no boundaries, and allows room for becoming.

*

I cringed at the midpoint of the film as a twenty-two year old, and I cringe at it now for different reasons. Then, I did not see what was coming when Ace and Tobio holed up in an abandoned house and kissed. Now, I see exactly what is coming. It is not just that I have seen the film before, it is akin to every trans reveal in every horror film in the ‘90s. I see what will happen before Tobio appears naked, bathed in light. I see the disgust on Ace’s face before it hits the screen. I have seen this moment in films like the infamous tuck scene in Silence of the Lambs, or the trans reveal in The Crying Game. Wild Zero, despite the ethereal light surrounding Tobio’s body, is not different.

But the discomfort is short lived. Ace is visited by the lead guitarist, Guitar Wolf, as he runs from Tobio and misgenders her. This is when the film’s salient line is delivered: Love knows no nationalities, borders, or gender. Guitar Wolf delivers it with a pointed finger and a guitar slung across his chest. There are likely flames in there somewhere. And Ace, who wants nothing more than to be Guitar Wolf’s brand of rock and roll, responds in kind. He saves Tobio once again from the undead.

Sitting here now, nearly forty, out of the closet, living alone in Cleveland, so unlike the rock and roll, drug-using, swaggering, scrawny twenty-two year old I was, I want nothing more than this kind of rock and roll to rule and save the world.

*

I can say I identify a lot more closely with Tobio watching this film as a trans adult, not a closted twenty-two year old. I can feel her moments, and I can feel her dejection. I can feel her grim resignation to the world around her, which is dangerous in so many ways.

But I’ve still got a soft spot for Ace. I can still see myself in his desperation to be the person he wants to be. I can remember the process of learning that rock and roll is not a costume, it’s, at its core, a kind of acceptance of possibility. In a world where zombies can roam the earth, misogynist club owners get their comeuppance, and a nerdy soft boy with a huge smile can become blood brothers with the coolest band he knows, how could you reject queer desire? How could you reject a body changing to become a real inner self? How could you deny this possibility?

Rock and roll, as Guitar Wolf says near the end of the film, knows no boundaries. Rock and roll gives us a chance to become, however we may do so. Maybe you, like me, are a person who was told they were female, who knew all along they were not, or, like Tobio, were assigned male at birth and knew that was a lie. Maybe you want more than anything to be like your heroes, or just something more true to who you are inside than who you walk through the world as. So be it. There is room for that in the world.

And may Guitar Wolf’s brand of rock and roll and acceptance help you get there.

Alex DiFrancesco is the author of Psychopomps, All City, and Transmutation. They ride a pink Vespa and live in Cleveland, OH.